As part of the 25th anniversary celebrations for Matrix Games, we will soon be releasing a new update for Strategic Command: American Civil War. Such an occasion deserves something special, which is why, in addition to the usual fixes and improvements, the next update will also include a free DLC campaign for everyone who owns the game: 1894 Imperial Twilight, covering the First Sino-Japanese War.

Wait, Doesn’t This Sound Familiar?

“History repeats itself” is, rather ironically, a hackneyed phrase. Every would-be tyrant since has eventually received comparison with Julius Caesar; every conqueror measured against Alexander. Napoleon’s imperial coronation was modelled on that of Charlemagne, and the American soldiers that invaded Mexico in 1847 took with them Prescott’s Conquest of Mexico as they hoped to follow in the footsteps of the sixteenth-century conquistadores. Usually such comparisons are of little value: Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812, for instance, shared little but geography in common with Hitler’s invasion in 1941, as they are often made purely for rhetorical point scoring.

But every so often, history does repeat itself. And of this, the Sino-Japanese War, and the Russo-Japanese War that followed it a decade later, may just be the most remarkable example of all.

In 1904, the Japanese surprised their enemies with a naval victory over a small enemy squadron near the key port of Chemulpo. This allowed them to conduct a nighttime disembarkation of part of their army, which briskly marched on Seoul and took the government of Korea hostage. The Combined Fleet moved the bulk of its strength into the Yellow Sea, where they blockaded the enemy fleet and prevented them from interdicting the transport of the IJA to Korea. Once deployed, the IJA marched through Korea, forded the Yalu near the fortified town of Antung, and routed their foes on the north bank. Dividing their forces, the Japanese would win a series of victories culminating in the siege and fall of Port Arthur, an advance on the city of Liaoyang and beyond, and the effective destruction of their opponents’ naval presence in Asia; victories won despite often being outnumbered, through a combination of skilled leadership, better equipment, carefully gathered intelligence and stronger morale.

And ten years earlier, they had done exactly the same thing.

The Sun (Begins to) Rise

Another hackneyed phrase worth repeating is that generals prepare to fight the last war. In 1904, that was true for the Japanese to a very literal degree: every Japanese unit would follow a route into battle against Russia that had been followed into battle against China – often the same units, often led by the same men.

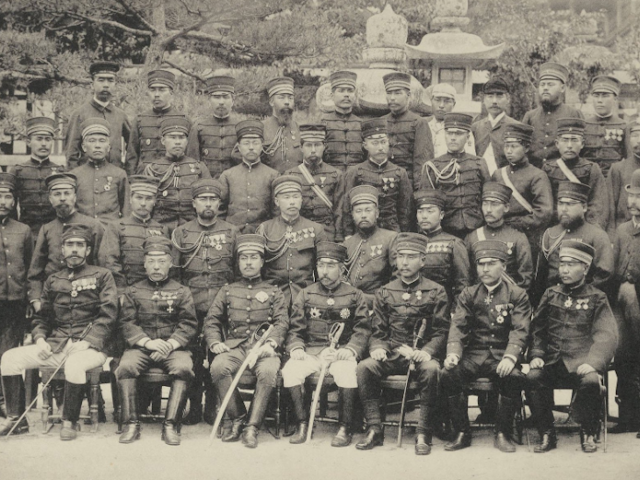

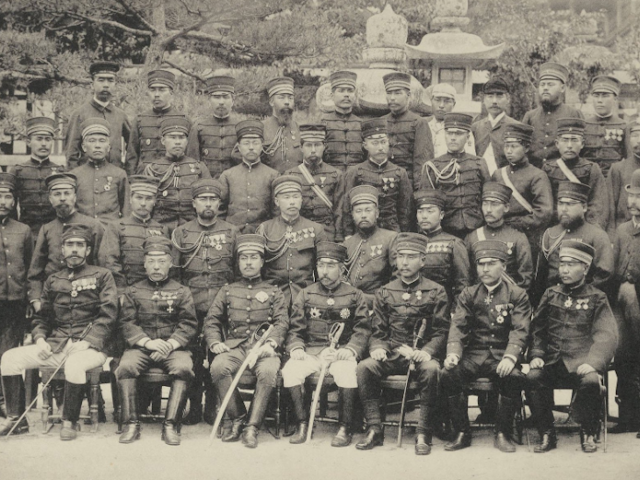

In 1894 however, Japan had no “last war” to look to. Abandoning an isolationist policy only with the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the country had embarked on an ambitious modernisation program, building up its industry, purchasing weapons from abroad and employing foreign advisors to train a new Imperial Army. Astonishing these efforts may have been, with the Emperor now commanding over 100,000 soldiers equipped with modern Murata rifles (whose design was inspired by, among others, the French Chassepot). The Imperial Navy too has been forged into a mighty force including six modern cruisers, and the first of the torpedo boats that would one day devastate the Tsar’s navies.

But the transition from isolation and feudalism to modern industrial power is one that took other nations centuries, and after 25 years it was hardly complete. Those soldiers have never been tested in a major war; those cruisers are surrounded by ageing ironclads and wooden corvettes including the Yamato and Musashi. In 1894, the precise mobilisation plans that would allow Tokyo to deploy its army to Korea, and take the fight to the Tsar in a matter of weeks, have only begun to be written; many of the transport ships have not yet been built. In embarking on a major war now, with the reform of the military not yet complete, the Japanese are taking an enormous risk.

Taming the Dragon

For all that can be said about Japan not being fully prepared for war, the situation on the other side of the Yellow Sea was arguably worse. While the Japanese government is united behind the Emperor Meiji, Chinese officials regularly ignore the Guangxu Emperor in favour of his former regent, the Empress Dowager Cixi. While the Qing maintain multiple armies and navies, disputes between the rival commanders ensure that only the northern army commanded by Li Hongzhang (Viceroy of Chihli and thus responsible for Manchuria), and the Beiyang Fleet, will be available for use in this conflict.

This period in China’s history is often depicted as a time when China failed to modernise, and was thus vulnerable to its more technologically advanced neighbours and suffered military humiliation as a result. There is an element of truth to this notion, as for instance Japan had rail lines covering much of the country by 1894 while China only had a short line running between the ports of Chinwangtao and Taku, but the Chinese efforts to modernise their forces should not be discounted either. On land, Li Hongzhang has improved the forces under his command to the point that there is no appreciable technological difference between the Chinese and Japanese armies. At sea, it may even be argued that it is China holding the technological advantage, with the Beiyang Fleet including two battleships – Chinyuen and Tingyuen – vessels that Japan has no clear answer to.

Unfortunately for China, the officials responsible for maintaining the fleet have done a deplorable job, having sold much of the ships’ ordnance and only recruited half of their crews (while drawing pay for a full compliment of sailors). The army is in little better state, poorly trained, led by incompetent commanders, and in dire need of reinforcements. China’s long coastline adds to the army’s difficulties, as they will need to defend not only Korea and Port Arthur, but also Weihaiwei on the Shandong peninsula and even the approaches to Peking itself.

In time, China may be able to resolve these problems – the Empire does command vast resources and will be fighting on home territory – but it is time that China may not have. The Japanese know of China’s many problems thanks to their spies, and have prepared for a quick war to achieve victory before Peking has a chance to respond. Of course, if they can’t achieve that quick victory, they could be in a great deal of trouble.

The Sunrise in the East

The main source I have used to design this campaign is titled “The War in the East” by Trumbull White, which was written either during or very shortly after the war – my copy, downloaded from the Library of Congress’ website, bears a stamp for July 30, 1895, just three months after peace was signed.

When I was reading up on the Russo-Japanese War, virtually every source I found made reference (usually several of them) to the preceding Sino-Japanese War and how the Japanese leveraged their experiences from 1894 to win again in 1904 – this account, being written between the two wars, only explores the Sino-Japanese War in its own terms. And yet even without the knowledge of future events, White still made two comments that I found particularly striking, and worthy of repetition. The first is:

“… the most pessimistic prophet could hardly have predicted the utter ineptitude of the Chinese military movements.”

It is easy to imagine Tsar Nicholas II – who took the throne as this war was raging – dismissing reports about the Sino-Japanese War as irrelevant when he began planning for his own war with Japan, as surely his “superior” European troops would be far more competent than the feckless Chinese. If he did, it would go a long way towards explaining why the Russians made so many of the same mistakes that the Chinese did. Yet I think it also makes a case for this conflict being worth exploring in its own right, rather than simply a prequel to 1904: this is a conflict that China arguably could have won with the resources they had available, and while historically the two conflicts proved very similar, it didn’t have to be that way. When you play this campaign, you will have the opportunity to see just how differently this war might have turned out.

The other line I will quote comments on the fall of Port Arthur: “The Japanese lost about fifty dead and two hundred and fifty wounded in carrying a fortress that would have cost them ten thousand men had it been occupied by European or American troops…”

When Port Arthur was taken again in 1905, White’s prediction would prove an underestimate.